The trend also seems to include more early season severe weather in the northern tier of the United States.

Big tornadoes have long been seen as being creatures of Oklahoma, Texas and Kansas. Think Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz.

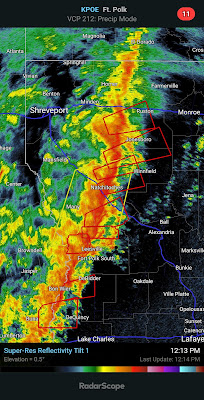

As I noted Tuesday, so called "tornado alley" has generally shifted eastward into the Gulf Coast States and Mid-Mississippi Valley.

The tornado targets are also shifting to places that usually feel safe from severe weather in the late winter and early spring.

One example happened on March 5 this year, when tornadoes swept across the Iowa landscape

One of the tornadoes, an EF-4 tornado packed winds of up to 170 mph and traveled along nearly 70 miles of Iowa farmland and towns. It was the first Iowa EF-4 tornado in nearly nine years, and the longest tracked Iowa tornado since 1980. As horrible as this tornado was, had its path been less than ten miles further to the northwest, it would have gone through the heart of Des Moines.

Another aspect of this tornado was it was the furthest north EF-4 tornado for so early in the season.

This is all just one more piece of evidence that severe weather outbreaks are shifting to new areas of the nation, and in those new northern locations, they are occurring earlier in the spring storm season, and later into the fall.

The anecdotal evidence, at least, is piling up.

Last March 26, a rare EF-1 tornado struck Middlebury, Vermont. It was the state's only recorded March tornado and easily the earliest in the season on record. That twister badly damaged one home and caused lighter damage to a handful of others.

On February 25, 2017, an EF-1 tornado with winds of up to 110 mph truck Conway, in western Massachusetts, seriously damaging six homes. It was by far the earliest tornado on record in Massachusetts and the only one to occur in February.

A tornado outbreak also struck Connecticut in May, 2018. Long Island and Connecticut also saw several tornadoes last November.

There's a pile of instances of newly destructive late fall and early winter tornadoes, too.

The most notorious of those was huge outbreak of straight line winds and at least 99 tornadoes that hit the central and upper Midwest last December 15.

It was the first December derecho on record anywhere in the United States.The 63 tornadoes that day in Iowa were the most for any day on record. Including the usual spring storm season. There was no record of Minnesota experiencing a December tornado until last December.

Back in the Northeast, nine tornadoes hit Long Island, New York and Connecticut on November 13.

Despite all these examples, linking tornadoes and climate change is tricky. The southeastern United States has always seen severe tornado outbreaks in the winter and early spring. Though you have to admit the tornadoes that struck Kentucky, Illinois and Arkansas last December 10 are easily among the most intense and deadly winter outbreaks in U.S. history.

There is reason to believe that climate change could be driving severe weather events northward, and causing them to hit earlier and later in the season.

As NPR reported last December, University of Michigan climate scientist Jonathan Overpeck is convinced there is a link between events such as the extreme tornado outbreaks last December 10 and 15 and climate change.

"The primary way climate change appears to be increasing thunderstorm and tornado intensity, especially in the cooler months, is simply because relentless warming is providing more fuel for these storms.

Warmer Gulf of Mexico waters mean more warmth and moisture for air masses moving north over land, where they collide with cold winter air moving southward, often setting up conditions needed for severe thunderstorms and destructive tornadoes. As global warming continues, we can expect these types of air mass collisions to occur further and further north, broadening storm risks to an increasing number of Americans."

In other words, Overpeck said, tornado alley is going to become bigger and year-round.

That said, warm, humid air from the Gulf of Mexico is only one of the critical ingredients needed for severe thunderstorms and tornadoes.

You need wind shear - wind that changes direction and speed with height - to get a good tornado outbreak going. Warm, dry air moving in from the west is often another factor that often feeds swarms of tornadoes.

Also, the way the cold air from the north interacts with storm systems can either energize or short-circuit tornado outbreaks.

Climate scientists haven't yet really figured out whether climate change will make these other pieces of weather more often contributors to severe storms, or will they more often stymie them.

As the Associated Press noted in December, less than 10 percent of all severe thunderstorms end up producing tornadoes. The understanding as to why a minority of thunderstorms spin off twisters while the rest of them don't is not entirely clear. So drawing conclusions about how climate change is influencing tornadoes is tricky.

A fair number of scientists think that climate change will increase the area of North America that most frequently receives tornadoes to increase, with the biggest spike in tornadoes coming in the fall and early winter. Much like we saw in the final three months of 2021.

What about us here in Vermont? Are severe thunderstorms and tornadoes increasing? So far I haven't found a clear trend.

I do know that severe thunderstorms are highly unlikely here in the depths of winter. It just never gets warm enough.

But with increasingly warm Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic waters influencing storms that pass over or near Vermont, you'd think that perhaps severe weather will increase. We'll never be Tornado Alley, that's for sure. Our location, geography and weather patterns would preclude that.

However, as we saw last March, and to a lesser extent last October, even here, we have anecdotal evidence that the summer severe storm season in Vermont is extending into the early spring and autumn.

Last year wasn't a particularly active severe weather season in Vermont, at least compared to the seemingly constant severe storms and even tornadoes from southern New England all the way down to Virginia.

There will always be a lot of year to year variability in the number of severe thunderstorms and tornadoes in any state or region. But several key factor seem to be making it more likely some of us will find ourselves cowering in the basement in the face of tornado or severe thunderstorm warnings.