|

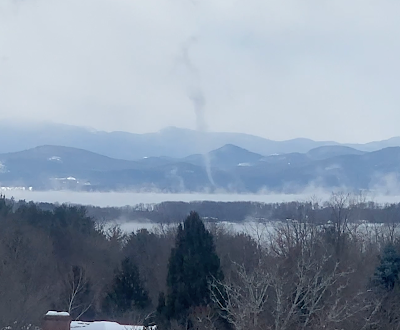

Vermont Gov. Phil Scott, shown here repairing

a neighbor's driveway after July's floods,

seems to work well with the National

Weather Service when coordinating storm

emergencies. responses. However,

politicians sometimes use the NWS as

scapegoats when an emergency response

doesn't go as well as hoped. |

"It came without warning," is the usual phrase we often hear after a weather disaster. Be it a tornado, wind storm, or flood, somebody will blame a meteorologist for not telling them danger was coming.

It's true that sometimes meteorologists, who are only human practicing an inexact science, indeed get it wrong. But often, the perception is at odds with the facts.

So it was in Maine last week.

The flood we experienced here in Vermont on December 18-19 was bad enough. In New Hampshire and Maine, it was even worse than what we experienced in the Green Mountain State. This was likely the second worst flood in Maine history. Only a 1987 flood was worse.

Which brings us to a tiff between Maine Gov. Janet Mills and the National Weather Service.

As the Bangor Daily News reports:

"'The National Weather Service did not predict five or six inches of rain in any community in Maine,' said Governor Mills Wednesday, speaking at a press conference after touring flood damage in Kennebec County."

But au contraire!

The National Weather Service in Maine rebuffed the governor. The storm was "well-forecasted and communicated in advance, including the potential for rainfall totals of 4-6 inches with localized areas receiving higher amounts," says the NWS.

The NWS noted that it provided forecasts and briefings to local and state officials starting on December 15, more than two full days before the disaster struck.

"In advance for the hazards that were likely to occur on Monday, December 18, NWS forecasters informed local and state officials in the days leading up to the storm through daily email briefing packages, direct phone conversation and virtual city and statewide briefings."

The NWS continued in their statement:

"The first flood watch and high wind watch were issued on Saturday afternoon, two full days before the storm. The state of Maine hosts a coordination call Sunday afternoon with NWS forecast offices in Gray and Caribou briefing on the expected flood, wind and coastal flood impacts. Rain began on Sunday bight, and by Monday morning NWS offices had issue flood warnings."

As you can see, the National Weather Service keeps all their receipts. There are many good reasons for this: Those receipts can clear up misinformation regarding their forecasts.

This really came in handy back in 2019, when then-president Trump said Hurricane Dorian was going to hit Alabama. A National Weather Service office in Alabama refuted Trump's claim. When they got annoying blowback (including through the infamous hurricane Sharpie map) from Trump and his MAGA minions, the National Weather Service was able to prove how their Dorian forecasts evolved. The NWS showed how and why they reassured Alabamans that the storm would be no threat to them.

There's another important reason for all those NWS receipts after a severe weather event. If their storm predictions turned out to be even a little inaccurate, the National Weather Service can use its huge paper trails to figure out went wrong to improve future forecasts. And how to better communicate with local and state leaders, not to mention the public.

The comments by Maine Gov. Janet Mills were not nearly as egregious as what Trump did there. Her criticism was pretty mild and fleeting. It didn't involve any direct interference in their operations. Politicians almost never go that far. Still, politicians will sometimes blame the meteorologists and their messengers if they mishandle a weather emergency.

Those politicians know screwing up a storm response can end their careers. Or enhance their careers, if they handle the emergency deftly. (To be fair to the Maine governor, the National Weather Service offices in Maine DID warn of strong winds, but those winds were slightly stronger than forecast).

Still, efforts by politicians to blame supposedly inaccurate weather forecasts are a tried and true way to go.

When flash flooding from former Hurricane Ida inundated New York City and took 13 lives of residents in the process, then-mayor Bill de Blasio said, 'Here's what we did not know, that we would have literally shocking and unprecedented rainfall," the mayor said after the storm. "No one projected that coming."

Only they did. The National Weather Service and other local meteorologists spent the days and hours ahead of the Ida flash flood pulling their hair out telling the public that the flooding would be especially severe and scary.

Here in Vermont, it seems like the state's political leaders have a good working relationship with the National Weather Service.

Prior to the Hurricane Irene floods in 2011, then-governor Peter Shumlin activated the state's emergency management center. He repeated NWS warnings of impeding severe floods.

Much more recently, just ahead of, during and after the state's devastating July floods, Gov. Phil Scott kept going out of the way urging Vermonters to take NWS weather forecasts and warnings seriously.

The day before the floods July 10 floods hit, Scott used National Weather Service's (accurate!) forecasts to declare a state of emergency, deploy swift water rescue teams around the state and warn people to be on guard and to take NWS flood warnings seriously.

The combination of the NWS flood forecasts, the Scott administration's reaction to those forecasts and media attention to all this likely saved lives. Two people died in the summer floods, which is obviously tragic. But a disaster of that magnitude "should have" created more fatalities. It didn't. The coordinated weather warnings between the NWS and Vermont leaders surely helped.

The December floods were a bit more complicated. Rainfall was slightly more than the NWS predicted and snowmelt was slightly more intense than expected. So the flooding that emerged that Monday was worse, somewhat catching the Scott administration by surprise.

But by late morning and early afternoon that day, Vermont emergency managers were on top of it. So was the National Weather Service office in South Burlington.

The bottom line is, the next time you hear politicians and even the public say the "storm came with no warning," check out the receipts from the National Weather Service. Sometimes they do botch a forecast, or don't issue a timely warning. But often, they're just a convenient scapegoat.